1800 words | 10 minute read

Content notes: mentions of trauma, suicidal ideation, domestic violence, sexual violence, CSA, state violence, cancer, and grief (none graphically)

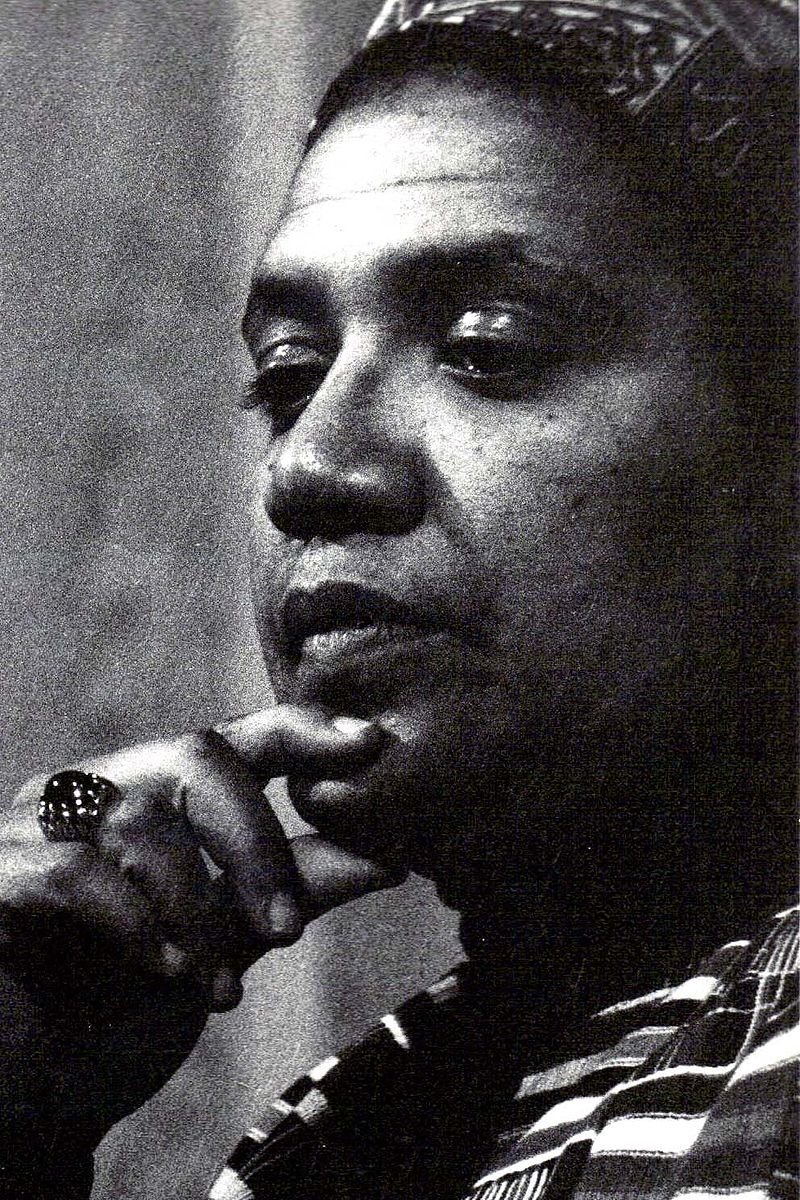

Image by K. Kendall, licensed under Creative Commons 2.0

I am suffering with grief at present. For those who follow me on Threads, you may have seen me post about the recent death of my grandfather, and now the impending passing of my uncle. Both have suffered, and my uncle continues to. Death, I have learned intimately now, may be a part of nature’s cycles, but it is not a pretty process. It is the raw, visceral, and destructive side of nature.

The grief is bringing out my trauma and it is a lot to contend with. As a survivor of domestic violence, too much sexual violence in adulthood to count the number of events, and childhood sexual abuse, I’m always running around up to my eyeballs in it. At the moment, though, it is feeling like even more to contend with than usual. The grief has brought down the barriers I have built over time, as battered as sea walls as they may be, that have sheltered me in such a way as to give some form of ‘coping’.

The suicidal ideation is back in full force. Pain and suffering and death feel inescapable right now, as do all my responsibilities and the money worry that comes from such a heightened cost of living crisis, and although I logically know I don’t want to die—I just want to escape—it doesn’t stop the thoughts from coming in and my mind ruminating on them.

It is times like this when I return to my favourite poem: Audre Lorde’s A Litany for Survival, which can be read in full here. As the Poetry Foundation describe Lorde:

A self-described “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet,” Audre Lorde dedicated both her life and her creative talent to confronting and addressing injustices of racism, sexism, classism, and homophobia.

Lorde was a remarkable woman. If you haven’t read any of her work—which includes essays and auto-fiction as well as poems—I would highly recommend her. Her Cancer Journals, described as “Moving between private experience and political analysis”, are pioneering in the field of autobiographical illness narratives. It is from her that we also get the phrase “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house”, meaning we must come up with creative solutions for the issue of collective liberation. She famously wrote the often-quoted “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare”, as esteemed feminist scholar Sara Ahmed shares on her blog (which builds on Lorde’s words to talk more about this self-care as warfare concept). Her writing on anger has also been hugely influential to me in my academic career. And A Litany for Survival remains my favourite poem.

Lorde was not just a writer. She was an activist in anti-racist, feminist, and queer spaces. She founded a press, along with Cherríe Moraga, called Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press. This was designed explicitly to publish more work by Black feminists. She spoke out about and campaigned against apartheid in South Africa. Unfortunately, however, her cancer returned in 1992 and eventually claimed her life. Shortly before, she took part in an African naming ceremony, taking on the name Gamba Adisa. This means “Warrior: She Who Makes Her Meaning Known”, a fitting name for such a pioneer and radical.

Why am I sharing this on a blog about paganism and witchcraft? Well, I personally get inspiration for my craft from many different avenue, and poetry—when I find the time to read it (it exercises my brain differently, and that can be taxing)—is an excellent source of inspiration. While I cannot share the whole poem here, I want to quote bits of it to explain why I think A Litany for Survival is the poem we all need right now, given everything that’s happening in the world. I’ll show how this relates to my witchcraft and religious practice, too.

The first part that always makes my breath catch in my throat is:

for those of us who cannot indulge

the passing dreams of choice

So many of us live without choice. Free will is pretty much a hoax: our autonomy is constantly impinged upon, no matter who we are, but some of us experience this much more than others due to the intersecting power structures of cisheteropatriarchy, ableism, white supremacy, and capitalism. Choice is a dream for us: I would love to choose to go to an art museum tomorrow, but given the limitations of my mobility, the inaccessibility of public transportation and buildings, and the associated costs, I cannot do this. Choice is a privilege. Choice is a dream.

So, too, can this be in witchcraft. For many of us, we are limited in how often we can work magic, whether that’s due to time, other responsibilities, or energy levels (or a combination of these). We often work the magic we need to, not what we want to. Who can work a glamour on themselves when they desperately need prosperity to walk through the door? Magic, as we see in historical folk practices, tends to fill a need. It is the tool of the oppressed, used to fight back. We cannot indulge in a fantasy world when the real one—and yes, it is a real one populated with various spirits and mysticism, still—needs our attention. We need to put the fire out before we can rebuild the house.

Lorde goes on:

For those of us

who were imprinted with fear

like a faint line in the center of our foreheads

learning to be afraid with our mother’s milk

Oppressed people grow up with fear deep within our bellies. Women and many non-binary people are taught how to stay safe from men: avoid dark pathways, carry your keys in your hand, and always tell someone where you are and who you’re with if you go on a date—and for the love of the gods, make sure it’s in a public place. People of colour, particularly young Black men, are taught by their parents that their skin might be a death sentence if the wrong cop pulls them over for a driving misdemeanour. They are taught how to be as submissive and ‘non-threatening’ as possible. LGBTQ+ people remember the fear of HIV and of ‘queer bashers’. Neurodiverse people mask, especially autistic people literally tortured through ABA ‘therapy’. I could go on.

To return to the poem, the first of two key proclamations come:

We were never meant to survive.

I remember first reading this poem and how the tears filled my eyes at this. So many of us really weren’t supposed to survive. For so many, we live in a society that disregards our lives, purposefully debilitating us and consigning us to what Lauren Berlant calls “slow death” [1]—if we’re lucky to even receive that.

I think that coming to terms with death as a process and as part of nature’s cycles, while hard (I mean, I’m struggling with it right now), is a crucial journey to go on as a witch. But to do this, we can’t just reflect on nature. We must see how certain deaths are encouraged or manufactured by an unjust society. Genocide is not a part of nature, but we are seeing it at present in many places, including Palestine. Death from environmental disasters brought on by human-made climate change is not natural. The extrajudicial murders of Black people in the streets are not part of nature. To truly understand death, we must recognise that there are both natural and unnatural deaths. To be a conscientious witch, we should work with nature’s cycles and work to prevent those deaths that are, in fact, an aberration to nature.

Returning to the poem once more, Lorde writes about the fear of things leaving or never returning: love, food, and the sun. When they come to us, we are terrified of losing them, wondering constantly how permanent they may be in our lives. When they do go, we worry they will never return and we’ll be left cold and alone. While these are things that naturally come and go in our lives, we are fearful of these losses, because they feel too much to bear when we’re constantly living in fear as people who were never meant to survive. We live in precarity, balancing on the edge of surviving or not, and so we inhabit the fear of loss constantly.

Lorde finishes the poem:

So it is better to speak

remembering

we were never meant to survive

I cannot stress how influential this has been in my life. I’m sat at my laptop, trying to find the words, but I can’t. I just stare at this ending and get all teary. It is a motto that I live by.

We should never have been silenced, but we have little to lose if we speak out. We’re not supposed to be here. However, here we stand, and so we should always speak, shout, scream if we have to.

I also think about the word “speak” and how it could be replaced with “act”. We should take action for the things we care about, including making a more equitable world. But this applies to our witchcraft, too. We are not supposed to be here, but here we are, and with our magic, we can properly take a stand. While we must back it up with material action, our magic is—again—the tool of the oppressed. Take that energy that you are only supposed to have in death and use it for some good. We do not have the luxury of choice, but as things in the world get progressively worse, we will have even less, and we will be living even more in the fear caused by precarity.

So act

remembering

we were never meant to survive.

Footnotes

- Berlant writes about obesity in a way that makes me, as a fat person, very uncomfortable. However, the theory that they put forward in the piece is sound and, indeed, adds much to our conceptual frameworks when discussing state policy and ideology that specifically seeks to disregard large swathes of the population.

If you enjoy my writing or find it informative, consider giving me a tip. I also have a wishlist of items that can be used for me to write new posts, and I’m always accepting ideas for these through the contact page. The wishlist also has things on there that are simply little treats to show me your appreciation.

I use YouPay, a newer platform, because it combines tips and wishlists, doesn’t reveal your legal name, and is sex worker-friendly, unlike most other platforms.

Leave a Reply